Understanding the MMT Curve

This article was originally published on eBooleant.com and is now part of the archive. Join readers concerned about how MMT is changing the investment horizon for bonds.

On July 18, Barron’s asked “The Deficit Could Hit $5 Trillion This Year. Are We MMT-ing Yet?,” to which we must answer yes. Clearly. MMT, Modern Monetary Theory, has taken hold, formally or not, on the globe. For the macro markets the belief is that virtually unlimited central government debt is the order of the day. Very high but non-inflationary levels are deemed good.

It is against this background that the U.S. Treasury’s June deficit hit a record of $864 billion. Meanwhile, the Congress is mulling the likely passage of a $3 trillion Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions Act or HEROES Act. Neither the current nor the projected federal deficits raise much opposition in Washington where both parties have adopted MMT-like programs. In fact, the HEROS Act has many supporters, including several prior Fed presidents who are actively advocating for it.

And for munis, the HEROS Act would surely be good news in the short run. It would come at an uncertain time for state and local government (See my piece, Waiting for Godot). The fiscal impact has received extensive coverage and conjecture. Less so is the systemic impact of MMT. It is imperative to consider what MMT is doing to federal/state relations and particularly micro market structure.

Massive federal budgets and an explosion of federal debt stand to shift federal/state relations from interdependence to irrelevance. Expansive federal assistance relieves us of the risk of a tsunami of bankruptcies of significant governmental entities, though smaller borrowers in the muni market remain at considerable risk. Here the comparison with the Great Depression is apt. In the Depression, thousands of municipal entities and one state went bankrupt. The New Deal changed this and helped to usher us out of a system of competitive federalism to more cooperative federalism. The states and the federal government were seen as having a shared responsibility in economic policy. Indeed, while the default experience of the Great Depression remains for some the gold standard of municipal credit analysis, it has little bearing on our current situation.

Enter MMT. The notion of cooperative federalism is shifting with the willingness of the Congress to expand the federal deficit in the recent period of great prosperity, and past today’s panic, to the unforeseeable future. We can get a glimpse of the policy implications of MMT in the treasury and muni bond markets. The treasury market is now four to five times the size of the muni market. Where will these markets be in ten years?

The states are going to continue to face the same structural borrowing constraints as they do now. It may even be worse. The record rainy day funds of a few months ago look like a pittance in many places now and will undoubtedly lead to even more conservative budgeting going forward. The muni bond market will, in all likelihood be around four trillion dollars in 10 years in real terms. The treasury market could easily be ten times that.

This should be considered in interpreting the muni term structure. A plethora of explanations exist for its slope and the recent rise in the steepness of the short-term rates. The simplest and most likely explanation, however, is a rise in expected inflation resulting from the growing federal deficit.

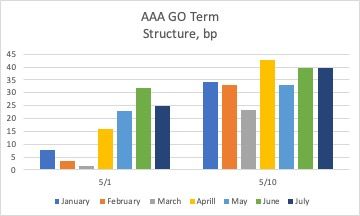

Chart 1 shows the slope of the Bloomberg AAA GO curve from one to five and five to ten years by month this year. The Covid-19 crisis has led to an accelerated increase in the size of the federal deficit and the treasury bond market. If one reads it as an MMT gauge, it suggests that MMT will continue largely unabated until we begin to experience a pickup in inflation five years from now. By that time, little that is unique to the muni market will affect its pricing.

We hope you enjoyed this article. Please give us your feedback.